Research

Understanding and treating refractory seizure disorders.

Seizure disorders encompass a wide spectrum, ranging from chronic epilepsy to acute and life-threatening presentations such as status epilepticus. Refractory epilepsy is typically defined as a condition of recurrent seizures that remain uncontrolled despite adequate trials of at least two appropriately chosen and tolerated anti-seizure medications (ASMs). Similarly, refractory status epilepticus refers to sustained or recurrent seizures without return to baseline despite treatment with 1st and 2nd line agents.

Numerous hypotheses have been proposed to explain the mechanisms underlying pharmacoresistance in epilepsy as well as status epilepticus. While no single theory fully accounts for the phenomenon, multiple mechanisms likely interact to produce treatment refractoriness in each case.

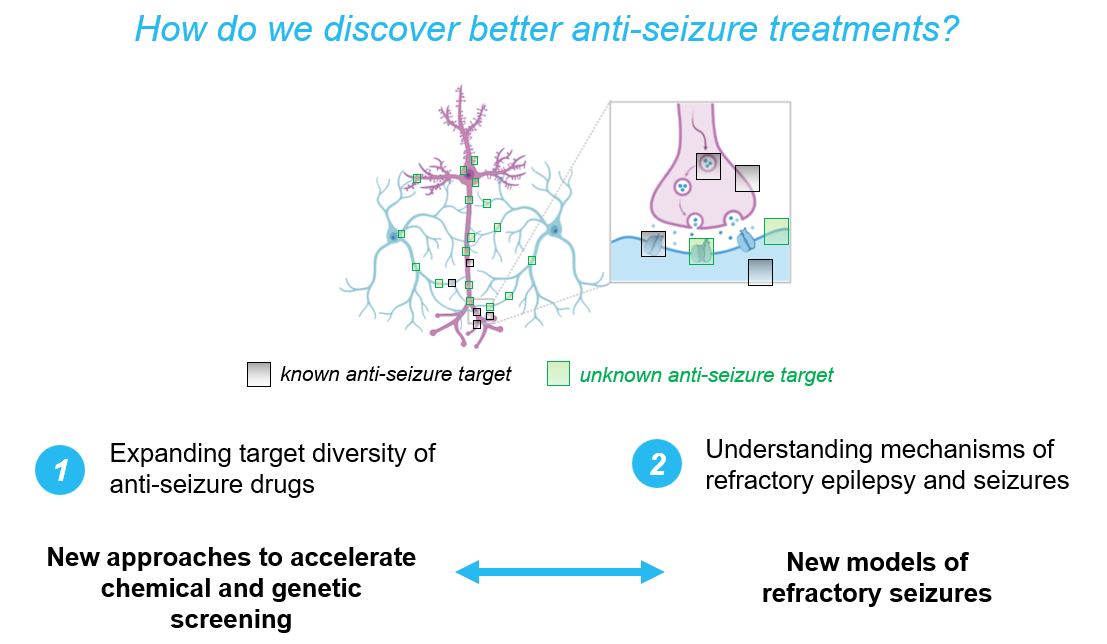

Our thinking on this topic is organized around a two-part framework:

- ASM failure may be attributed, in part, to the limited diversity of molecular targets among currently approved ASMs, and

- Refractory seizure disorders involve pathophysiological mechanisms that are distinct from those in more treatment-responsive forms.

The origin for this thinking begins with the fact that most currently available ASMs were identified through phenotype-based screening paradigms, in which compounds were selected for their ability to raise the seizure threshold in otherwise healthy animal models (e.g., phenytoin in the maximal electroshock seizure model in cats). These approaches have been effective in yielding drugs with broad efficacy against human patients with seizures, with roughly similar response rates for both chronic epilepsy (~60%) and status epilepticus (~60%).

However, the effectiveness of these compounds may depend on a range of underlying physiological parameters being within normal limits — conditions that may not hold in individuals with refractory disease. In such cases, resistance may arise from alterations in these physiological baselines, due to a combination of:

- genetic factors, ranging from common polygenic risk alleles to rare, high-impact variants,and/or

- acquired pathological changes at the cellular or molecular level.

In addition, there may be many viable anti-seizure targets the field has not yet discovered, as it is unlikely that the phenotypic screening performed to-date has exhaustively covered the target space – and phenotypic screening has still only rarely been performed in refractory models themselves. In contrast to other fields of medicine where sustained efforts to identify novel therapeutic targets have yielded significant advances (such as oncology), the pursuit of new molecular targets in seizure disorders has lagged behind. This relative lack of emphasis may stem, in part, from the perception that the most relevant targets—such as sodium channels, GABAA receptors, and glutamate receptors—have already been identified and explored.

These considerations lead us to the main overarching interests of the lab to:

- develop novel models of refractory seizure disorders for mechanistic insights and for screening

- characterize and control the molecular determinants that modulate seizurogenesis and the efficacy of existing ASMs

- develop and test novel neurotherapeutic approaches

Novel models of refractory seizure disorders

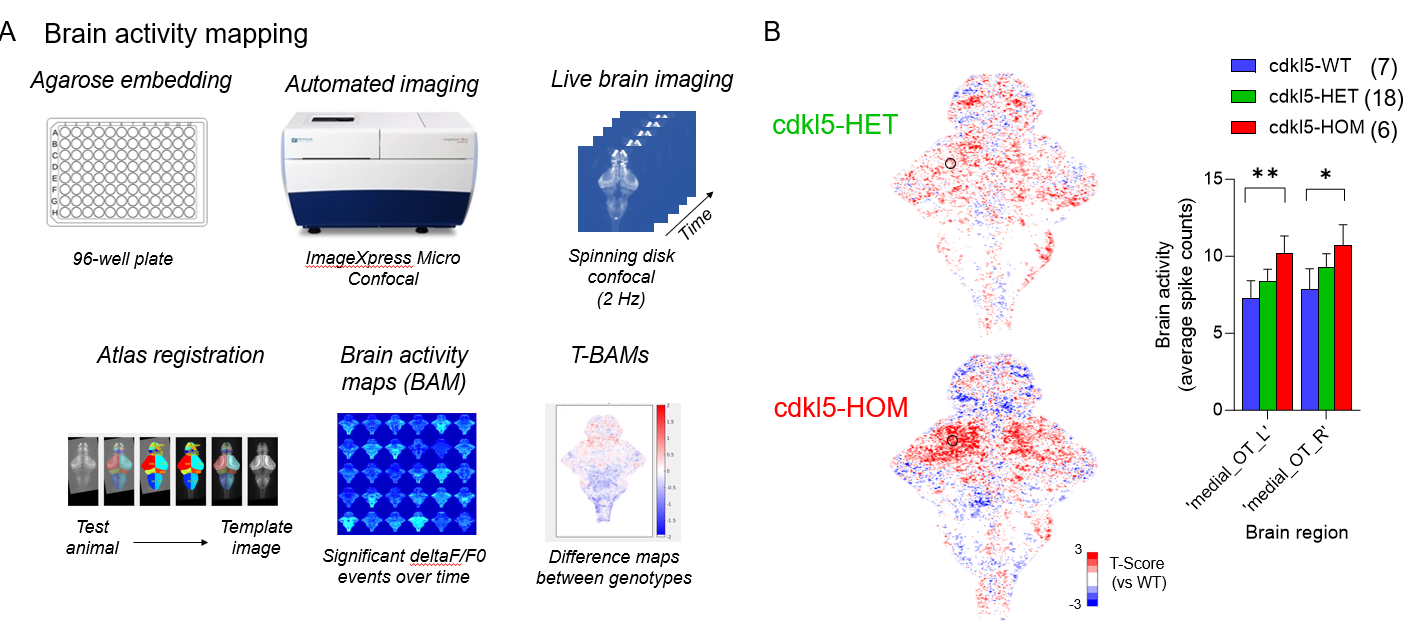

Animal models provide a powerful tool for dissecting the unique pathophysiology of refractory seizure disorders, and for testing therapies. In particular, the use of zebrafish allows for rapid chemical and genetic screening over 100s of fish, massively increasing throughput over larger vertebrates, while being more biologically authentic than cell-based models. The McGraw Lab is interested in developing models of 1) refractory chemical seizures, and 2) refractory genetic seizures.

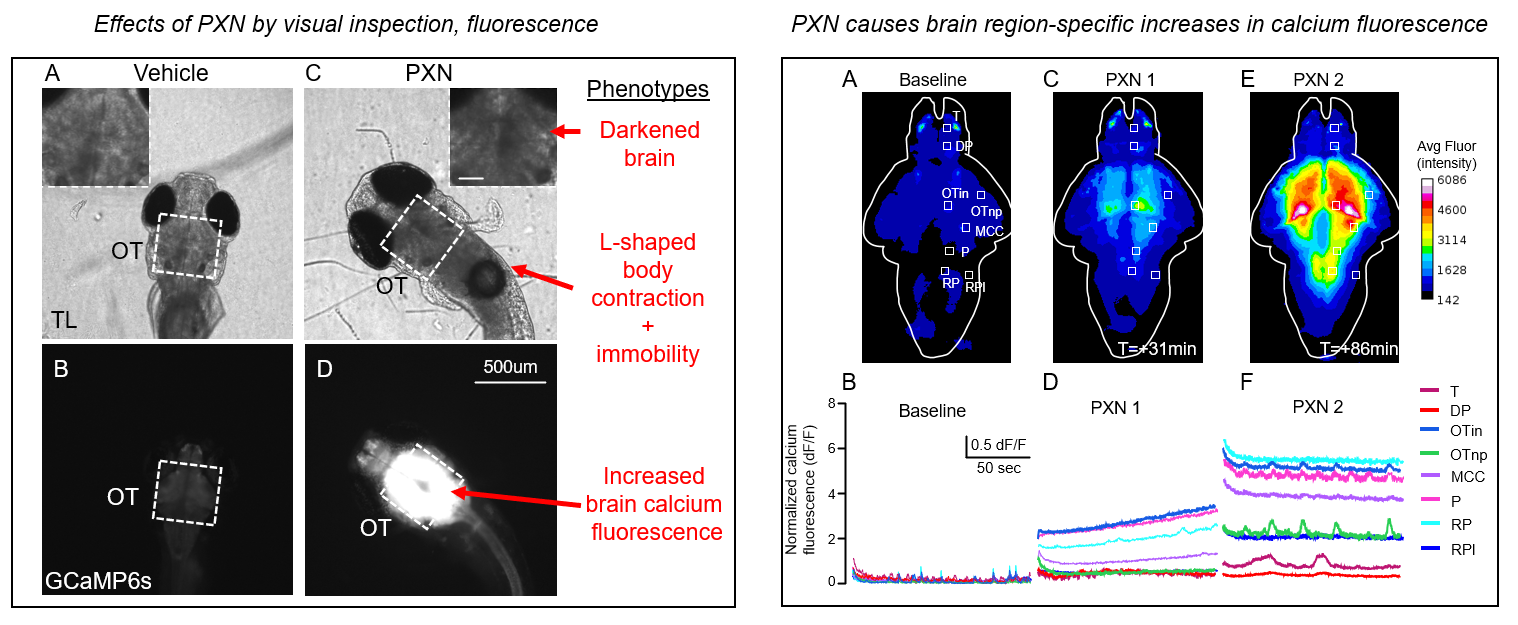

Through the first approach, the McGraw Lab has developed an organophosphate (OP) model of status epilepticus (SE) in zebrafish (in preparation) supported by the NINDS / NIH CounterACT initiative. This model displays hallmark signs of SE including body contracture and increased brain calcium fluorescence, which can be assayed non-invasively in 96-well format using methods we previously developed for combined movement and calcium fluorescence profiling. The pharmacology appears similar to OP-related seizures in rodents and humans, including strong reduction by NMDAR inhibition (MK801) and resistance to benzodiazepines (DZP).

Additional future directions include: understanding the cellular/molecular mechanisms of OP-related seizures, including the role of inflammation and BBB breakdown; long-term sequelae on epileptogenesis; and the effects of specific targeted interventions on OP-related seizures in our model and their translation to mouse.

In the second approach, the McGraw Lab has developed multiple zebrafish models of neurodevelopmental disorders that feature epilepsy (genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of GAT1; CDKL5), however our results have been more modest.

In CDKL5, these fish do not display spontaneous seizures or tectal epileptiform discharges (in preparation), but brain activity mapping demonstrates tectal hyperexcitability. Preliminary evidence suggests this may be due to elevated number of excitatory synapses in optic tectum.

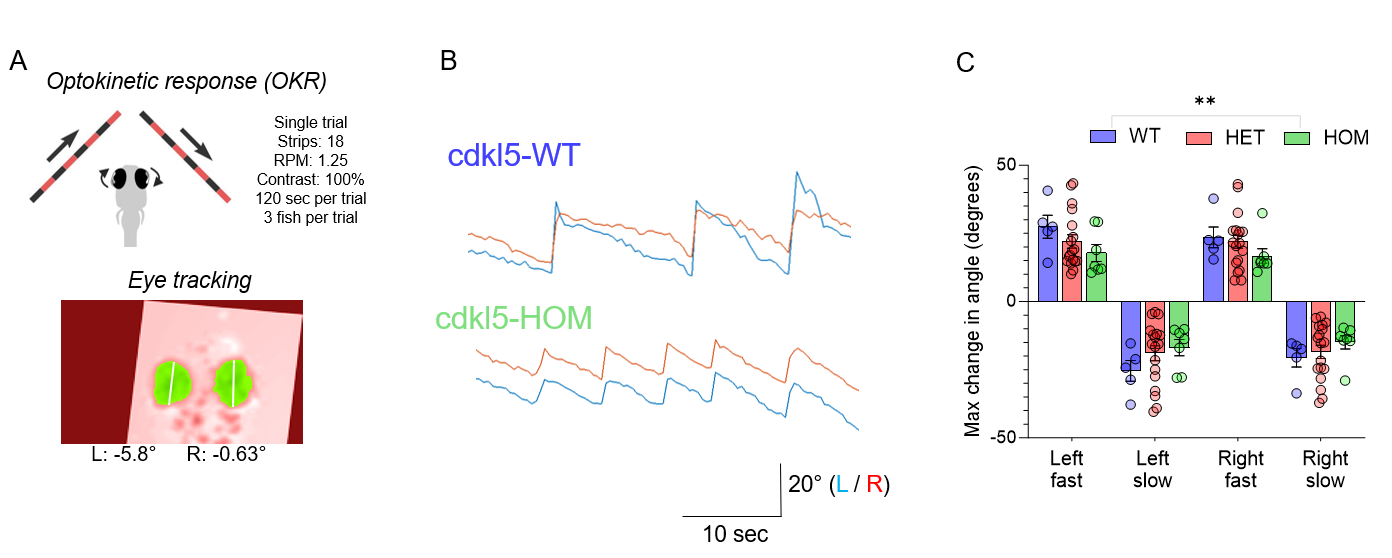

In addition, cdkl5 knock-out fish demonstrate abnormal optokinetic responses (OKR) – a visually evoked response, also impaired in cdkl5 mouse and individuals with CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder.

We plan to use our model to further understand the molecular function of cdkl5 in hyperexcitability and visual dysfunction, and to assess the response to mRNA rescue with human CDKL5 variants. This work has been supported by the LouLou Foundation.

Molecular determinants of seizure disorders, and seizure severity

Dr. McGraw is a contributing member of the ILAE Consortium on Complex Epilepsy, and the Epi25 Collaborative – two large international initiatives dedicated to the genetics of epilepsy. He is also a contributing member of the Yale NORSE Biorepository

The McGraw Lab is currently conducting a clinical study to evaluate whether polygenic risk scores improve our ability to predict seizure severity and/or pharmacoresistance in adults with acquired focal epilepsy.

We have also developed assays to functionally validate human variants. One of these is a cell-based fluorescence assay for human GAT1 function (in preparation), which we have shown accurately predicts pathogenic variants and resolves variants of uncertain significance.

Another approach to functional validation is using zebrafish models using the human mRNA rescue paradigm. In this approach, the ability to rescue phenotypes observed in cdkl5 zebrafish using WT or mutant human CDKL5 mRNA provides a rapid means to connect genotype to phenotype, and set the stage for additional molecular investigations.

Neurotherapeutics

We hope that our research has human translational impact – the strongest indicator of which is whether new therapies identified and/or tested in our preclinical models reach human trials.

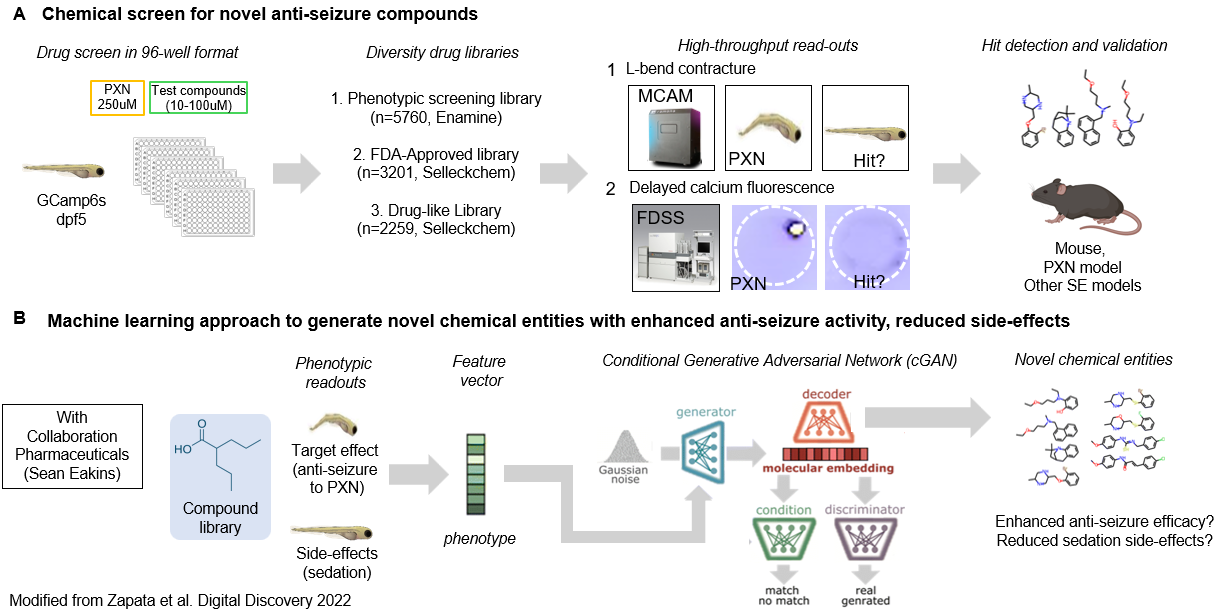

We are still at an early stage, but we plan to perform target discovery and compound discovery using our PXN model of refractory status epilepticus to identify seizure-specific counter-measures. We also hope to leverage screening data for machine-learning models for additional in silico methods.

Using our non-radioactive hGAT1 assays, we also hope to partner with drug discovery programs to perform compound screening for positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) which may have therapeutic applications for developmental epileptic encephalopathy (DEE) and other neuropsychiatric conditions.

Lastly, regarding CDKL5, we hope to deploy a compound screen to improve vision-based phenotypes in our cdkl5 zebrafish. In addition, we are testing the efficacy of genetic ‘prime editing’ in a Cdkl5 mouse model, supported by the Loulou Foundation.